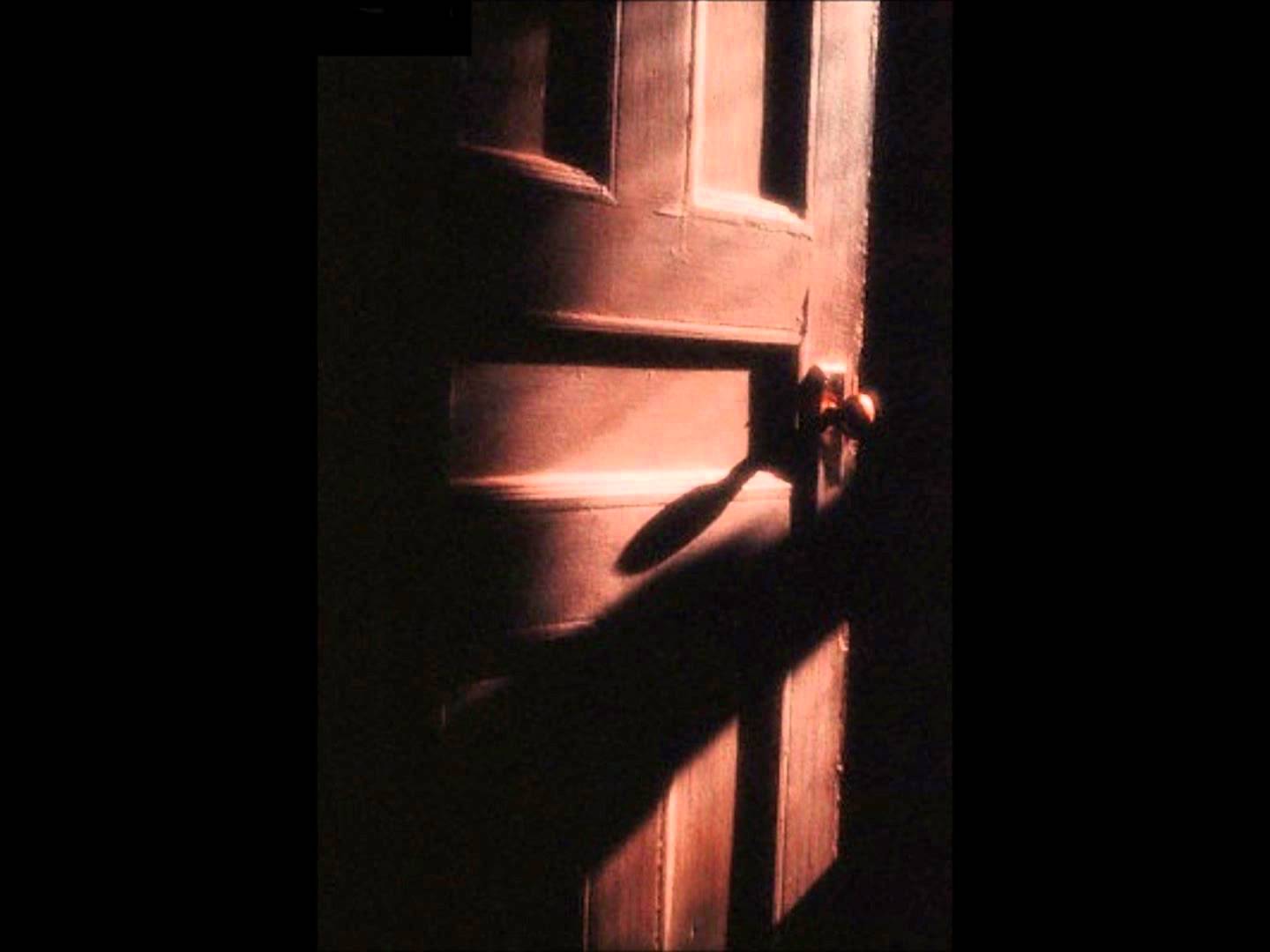

A well-intentioned “Open Door” policy can become its most problematic policy. The purpose of these policies is to foster communication between rank and file employees and management in order to share ideas and to address issues of concern such as safety, productivity, pay, etc. So far, so good. (Most companies have separate policies and procedures distinct from the Open Door policy, which allow employees to lodge formal complaints about safety violations or discrimination and harassment issues for formal investigation.)

A well-intentioned “Open Door” policy can become its most problematic policy. The purpose of these policies is to foster communication between rank and file employees and management in order to share ideas and to address issues of concern such as safety, productivity, pay, etc. So far, so good. (Most companies have separate policies and procedures distinct from the Open Door policy, which allow employees to lodge formal complaints about safety violations or discrimination and harassment issues for formal investigation.)

As with most issues inside organizations, it’s not the Open Door policy itself that’s the problem – it’s the implementation. Sadly, most organizations are unaware that their desire to foster open communication between employees and management actually fuels drama and a lack of accountability. This occurs because most Open Door policies are mismanaged by overly-helpful supervisors and used by unhappy employees who didn’t get what they wanted. The result is a lot of unproductive conversation and reinforcing the notion that complaining employees simply need to dump their unhappiness at a supervisor’s feet in hopes that the supervisor will charge off and give a co-worker or a lower level supervisor “what for”.

Common issues that come through the “open door” sound like,

• “My co-worker (or supervisor) is mean to me.”

• “My supervisor won’t let me take vacation.”

• “Sally doesn’t pull her weight, and I’m tired of doing her job.”

In my experience, the most common misuse of the Open Door policy occurs when an employee disagrees with something that’s going on and believes his perspective is the right perspective, while everyone else is to blame. This could involve anything from disagreements with a co-worker to disagreeing with decisions made by a supervisor, receiving negative feedback, disliking an assigned task, or being denied time off. In these situations, no policy has been violated, and there is no inappropriate supervisory behavior (although the employee might intimate there is). The employee simply doesn’t like what a co-worker or supervisor communicated, decided, or assigned. So the unhappy employee goes shopping for a sympathetic ear and someone to solve the problem.

This is highly problematic as it usually sucks everyone into a drama triangle. The employee, playing the role of Victim, complains of a co-worker or supervisor, who is (often unwittingly) cast in the role of Persecutor because he interfered with something the employee wanted. The unhappy employee walks through the “open door” as Victim to visit a supervisor, seeking a Rescuer, who will heroically step in to save the day, magically solve the employee’s problem, and right the alleged “wrong”. And most supervisors take the bait and are easily sucked into this.

Meanwhile, work has been interrupted and productivity declines.

With a little boundary setting and just-in-time employee coaching, these types of situations can be diffused and turned around relatively quickly with the employee retaining the responsibility for accounting for their own behavior and solving their own problems. Here are some tips to avoid drama, empower employees, reinforce accountability, and avoid being dumped on, triangulated, or manipulated into Rescuer mode:

1. Stop Interpreting the Term “Open Door” Literally.

An Open Door policy does NOT require managers to keep their doors open 100 % of the time and be 100% available to 100% of everyone who stops by. This is highly inefficient and not helpful.

Instead, an “open door” signifies an open attitude to discussing issues of concern with employees. This may mean that an employee schedules a time to talk, or that the employee meets with the manager during specified “Open Office Hours” when employees are indeed free to drop by without appointment.

Making oneself so accessible only trains employees to reactively run to managers to have their problems solved for them. In fact, it’s likely that managers who make themselves so available have a need to be needed. Having to wait even an hour to meet with a manager can sometimes calm an employee enough that he decides the issue isn’t worth involving someone else.

2. Inform Your Team of Your Availability.

Let your employees know when you hold “open office hours” with no appointment needed or that they should schedule a time to talk if necessary. It’s also good to make sure every understands the signs for when you are not available, such as a closed door, closed blinds, etc.

3. Ban Your Inner Rescuer and Learn to Act as a Coach.

Need to be needed? It does feel good to be the one to save someone in distress, but that’s not the job of a leader. Instead, as a leader, you are charged with building the capacity of everyone you work with, and capacity is not built by solving issues for others or saving them from uncomfortable circumstances that they can work through on their own.

Rather, you build capacity by assisting others to examine the situation, list options, and choose something they can do to address the situation. For example, instead of getting mad at a co-worker for something that didn’t happen or went wrong, the employee might be better off asking the co-worker what she can do to help, so that situation doesn’t happen again. Alternatively, guided by a supervisor’s questions, the employee may decide the issue is more appropriately raised in a team meeting.

The worst thing a leader can do is to intervene on behalf of an employee and inadvertently send the message that the employee is not capable of solving most of her own issues.

4. Train Supervisors.

Make sure your supervisors understand all workplace rules, policies, and procedures, so they are less likely to run afoul of them to the detriment of their direct reports. Also, train supervisors to coach employees through issues so they do what they can within their control. This builds even more capacity within the organization.

5. Require Both Parties to Take Issues Up the Line of Report Together.

Under an Open Door policy, the vast majority of issues will go away if you require the employee (and supervisor) to be accountable for what she can do within her control under the circumstances. Unfortunately, many companies unwittingly reinforce the notion of employees as victims by allowing and even encouraging a complaining employee to circumvent the immediate supervisor and to meet with the boss’s boss (or higher) to complain under an Open Door policy. This simply reinforces the drama triangle dynamic.

In fact, I have never seen an issue come up through an Open Door policy that couldn’t be solved by having the parties examine their own capability and accountability.

For the sake of argument, if an issue appropriately escalates up the chain of command, require the parties to shepherd the issue to the next level together. This reinforces the assumption of trust between employees and management and avoids the triangulation that can occur when only one side of the story is presented in isolation. To reiterate, the overarching theme should always be to put the accountability squarely back on the shoulders of each person involved.

No one wants to see anyone in the workplace treated unfairly or to have unaddressed issues negatively affect the work. Mechanisms, like Open Door policies, that encourage raising issues for resolution are necessary. However, when the way in which we implement such policies reinforces notions of disempowered victimhood and allow for unproductive drama to get in the way of priorities and focus, it’s time to step back and determine how all employees can be encouraged to be accountable, especially when things don’t go as planned.